Faster, Better, Cheaper

As advocates of former NASA Administrator Dan Goldin's 'Faster, Better, Cheaper' mandate, my colleagues and I were often viewed as loose cannons. We contended that all three objectives were achievable simultaneously, in contrast to the prevailing institutional view that only two could be pursued at once.

While navigating the Byzantine Flight Certification process, I sent a frustrated email to a senior colleague with expertise in Flight Safety. His response has stayed with me:

'Much of what you point out is correct, but remember that these regulations stem from hard-learned lessons. None are arbitrary or ill-conceived. Reform demands meticulous effort, addressing one rule at a time.'

Is 'Proven' Truly Superior?

Over the course of my career, I saw a gradual calcification of workflow, suffocating innovation. Each year, it became one step harder to do anything. The reasons for each new obstacle always made sense and mainly revolved around either assuring that we complied with a policy or process directive or thoroughly coordinated with all possible stakeholders. Process and policy directives contained many steps - each of which completely rational, sensible and reasonable.

But the sum made progress slow and expensive. More importantly, it gave rise to work-arounds that often resulted in 'legal' solutions that were inferior engineering solutions.

The cost and schedule to develop a new, optimal solution to a problem often pushed managers toward brittle kludges made up of existing, certified components.

Certainly not what we wanted to happen, but an all too common occurrence.

Another result was that as the process lengthened, testing became more expensive in terms of cost and schedule. As processes extended, analysis increasingly replaced empirical testing.

This is the root cause of the delays stemming from inadequacies in the thruster systems of Boeing's Starliner and Sierra Space's Dream Chaser.

This path is not leading NASA to be Safer nor Cheaper nor Faster.

Surgical Litigation

The problem with trying to surgically trim and improve the myriad processes at a large and historic place like NASA is that almost all processes make sense. Each step is rational and usually based on painful experience, as mentioned earlier. This makes the innovator into a prosecutor, trying a case against an innocent requirement. You have to win that case and a thousand more.

This is an impossible task, made worse by the fact that the processes and regulations keep increasing.

As the number of processes, regulations, organizations and requirements grows, the need arises for people to manage the processes. This grows into teams. For these folks, ensuring compliance to the process is their product - they are by definition somewhat removed from the actual product, be it spaceships or software. These process engineers attempt to add value by creating ever more processes. Each one is more complex than the last and backed with strong logic.

My conclusion was that you have to blow up the whole thing and start afresh. I was in a position to exercise an abnormally large amount of process discretion in my organization and promptly disregarded the majority of legacy processes. As I expected, the result was buggy, late software releases and a lot of criticism.

But this was a necessary step to create new processes informed by current experience and tested by measured performance. We soon doubled our output and halved our discrepancies.

The question then, is how do you do this with safety critical systems? How do you do it with long lead hardware?

Enter The Disruptor

SpaceX is showing the way forward. The company was created in a silicon valley software mold: build a prototype as quickly as possible, accepting the near certainty that it will fail. Observe the failures, improve the design and iterate until optimized. That path led to the Falcon and Dragon - easily the most successful LV in history.

In January, I attended a gathering to celebrate the 25th anniversary of continuous human presence on the Space Station. I brought up SpaceX's success to a colleague, who said that it was good for them because they can afford to do it that way. 2 years ago, I heard the same from a Lockheed Martin VP.

But is any of that true?

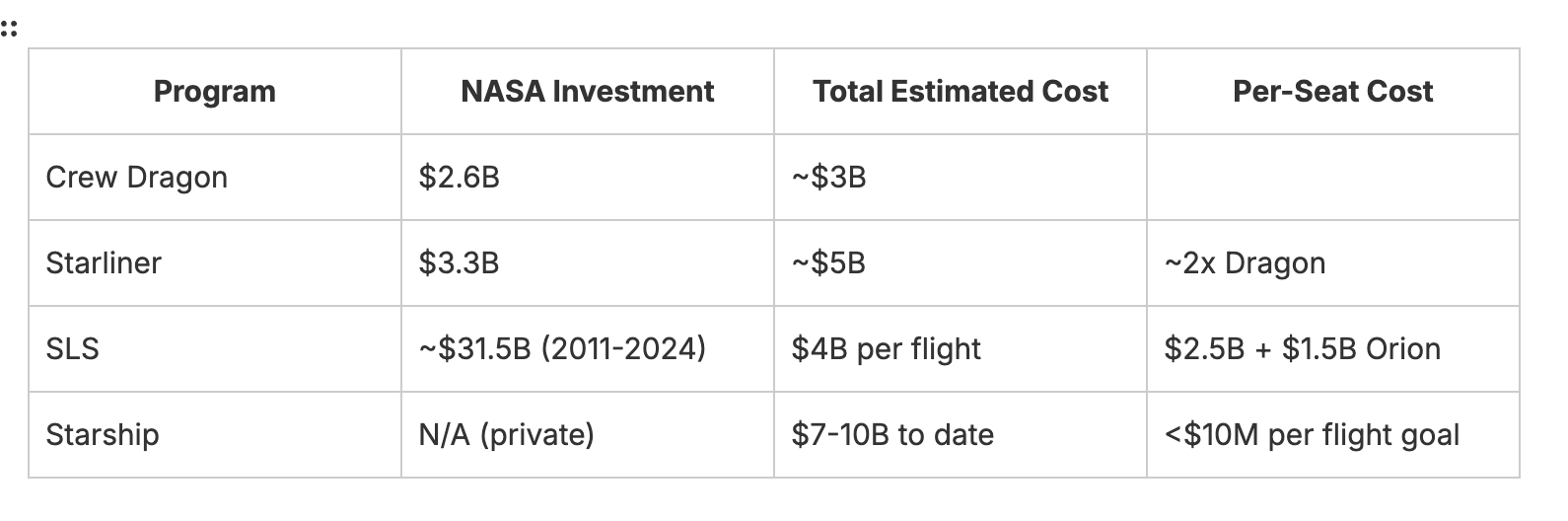

Comparing Crew Dragon to Starliner provides a stark contrast. Starliner's dev cost and operational per-seat costs are nearly double those of Crew Dragon. The disastrous flights of Starliner, culminating in the crew being stranded on ISS, offer testament to the superiority in Safety of the SpaceX approach.

Consider the SLS which will be sending the Orion capsule and 4 astronauts around the Moon and compare it to Starship.

In typical NASA fashion, tying down an actual cost for SLS is difficult - are you talking about the core vehicle, the upgrades, ground systems, etc? Each is tracked separately and often Congressionally appropriated separately. One could make a career of just trying to figure out what things actually cost.

In the end, we can say that the cost from inception in 2011 thru first flight in 2022 was likely about $23B. Since then, a further $8.5B has been spent. Per flight costs moving forward are roughly $2.5B per LV, plus $1.5B for Orion and operations, totaling around $4B.

Estimating Starship costs is more speculative because SpaceX is a privately held company. Estimates to date range from $7B to 10B - far, far lower than SLS. These costs include construction of the Starbase and launch pads, which SLS did not incur because it uses Apollo/Shuttle facilities at KSC.

Of course, Starship is not complete, nor is it close to being human rated. But if one projects the cost run and progressive performance improvements, it is very unlikely that it's total cost will even approach SLS when it achieves human rating.

More telling, Elon has repeatedly stated their focus on a design and infrastructure that can support very high launch cadence and per-flight costs under $10M.

SLS missions cost 400X as much as Elon's planned Starship missions.

Can you think of any cost disparity this large between competing products?

The Way Forward for NASA

New Administrator Jared Isaacman has the right perspective and goals. He will need help from an army of followers inside the Agency, empowered to do what I did in my software team. They will need to abandon incremental process reform and be very aggressive in deleting requirements and processes.

One possible path would be to create competing projects, one following the existing processes and one iteratively innovating. This would need to be focused on smaller projects, as standing up duplicate pairs of billion dollar programs is not feasible. But momentum could be initiated in this manner.

Crucially, Isaacman will need to be decisive and uncompromising - firing many experienced senior. leaders who undermine the efforts. No matter how much potentially valuable experience they might have, no matter how well meaning, it is those middle managers who stand in the way of a revitalization of NASA.